Cross-border lawfirm websites differ significantly when it comes to cookies and privacy

Most large law firms are advising their own clients about data privacy generally, and the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in particular, so their own websites may offer useful perspectives on data privacy compliance.

The data privacy stakes

On the risk side of the data privacy ledger, under the GDPR regulations that came into force in May 2018, websites that target European clients can be fined up to 4% of global revenue for breaching GDPR and of course there are local data privacy regulations in non-European countries too. To simplify things we’ll also accept the common argument that GDPR is important as the overarching data privacy standard to reach and that GDPR is likely to be influential in the formulation of numerous national privacy policies.

On the reward side of the ledger, website analytics data represent one of your biggest and most important sources of data about the market – for very large lawfirms literally millions of unique visitors annually.

Depending on how individual firms interpret privacy compliance they can labor under significant competitive disadvantages versus other firms who think differently, as you’ll shortly see.

Why cookies specifically matter

Cookies are an important piece of web wiring and are typically used by lawfirms in one more of the following ways:

- Website analytics packages like Google Analytics (to identify repeat visitors – which includes your clients)

- Social plugins like Facebook’s ‘Like’ button where they identify individuals personally as they move around the web

- Re-marketing (you visited my lawfirm website and now I”ll display banner ads to remind you of that as you visit other websites)

- Session management and other website ‘infrastructure’ uses (only cursorily covered here)

In analytics projects for professional services firms we quite commonly see 10 or more different cookies being set when you visit a site’s homepage and some lawfirm sites that list the actual cookies they use (across all pages in the site) will list dozens.

From a regulatory perspective the European Commission appears to rank cookies right up there with home address as an example of personal data and website developers often advise our lawfirm clients that they need cookie consent code incorporated during site revamps. Whilst still other developers sell plugins to manage cookie consent for common CMS platforms like WordPress.

In summary, the regulatory regime, website developers, and conflicting advice on the web, has created not a little concern and a high degree of variability in how cookies and consent are treated on lawfirm websites. And if that’s the case on lawfirm sites (who will be better placed to understand the regulatory landscape) then other websites have a much bigger problem.

The three models lawfirms use for cookie consent

We typically see three main models used on lawfirm’s websites based on Magnifirm’s testing across large and small firms (we also tested the global top 10 lawfirms by revenue to see if there was any difference based on size of firm) along with day to day analytics work we do.

We checked what cookies were placed, in what circumstances, and just in case firms were using geo-ip location, we tested using European IP addresses. Finally, we focused this informal study on lawfirm websites who had offices in multiple countries, including Europe.

Model 1: Browser-wrap implicit consent (50% of websites and the most common model)

Used on about 50% of lawfirm websites there is no overt popover cookie banner but instead the website links to a privacy policy in the page footer. If you navigate to the privacy policy it has a section dealing with cookies and their usage by the website and sometimes links to instructions generally available on the web for disabling cookies. Here’s an actual example:

Does browser-wrap implicit consent meet GDPR requirements?

If cookies of the kinds we have described above are personal data (and that’s a key question we’ve covered before specifically on Google Analytics) to cut a long story short it doesn’t seem likely browser-wrap implicit consent works under GDPR. There’s no clear affirmative acceptance, the website is (largely) ‘silent’ about cookies, and inactivity leads to the cookies being placed by default.

But judge for yourself from what GDPR Recital 32 actually says about consent –

Consent should be given by a clear affirmative act establishing a freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her, such as by a written statement, including by electronic means, or an oral statement.

This could include ticking a box when visiting an internet website, choosing technical settings for information society services or another statement or conduct which clearly indicates in this context the data subject’s acceptance of the proposed processing of his or her personal data.

Silence, pre-ticked boxes or inactivity should not therefore constitute consent.

Consent should cover all processing activities carried out for the same purpose or purposes.

When the processing has multiple purposes, consent should be given for all of them.

If the data subject’s consent is to be given following a request by electronic means, the request must be clear, concise and not unnecessarily disruptive to the use of the service for which it is provided.

To underscore the view that browser wrap implicit consent is potentially problematic under GDPR we found that 2/3rds of lawfirm websites using browser-wrap implicit consent place cookies immediately on landing on the website i.e. before visitors have the chance to read and find the privacy statement (if you were so inclined). Only 1/3rd of browser-wrap implicit consent lawfirm websites placed cookies on the second page visited (but not on the first) which perhaps might help these firms make a consent argument …. somewhat.

Model 2: Cookie-banner implicit consent (40% of websites)

Used on about 40% of the lawfirm websites we tested, this model pops up a banner at the top or base of the page as in the example below. In a nutshell this model says ‘if you click OK, or keep using our website, we will consider that cookie consent‘ and there’s no option to decline cookies except by disabling them in your browser (as with browser-wrap implicit consent).

90% of these lawfirms wrote cookies on the first page visited before you had the chance to click Ok to consent or to leave the site. The other 10% wrote cookies on the second page visited (most sites keep the banner up until you dismiss it).

Does cookie-banner implicit consent meet GDPR requirements?

At least this consent model is much more overt in drawing website visitors’ attention to the fact that cookies are being used.

However it still does look rather like a “pre-ticked box” under GDPR Recital 32 quoted above and in nearly all cases the cookies are being written anyway on the first page, and on all subsequent pages after the first page, whether you click ‘ok’ or not.

Also, having a statement on the website implying ‘you can’t use the site unless you accept cookies’ might be problematic given GDPR Recital 32’s warning that consent must not be “unnecessarily disruptive to the use of the service for which it is provided” (it seems somewhat disruptive to say that you just can’t use the site without cookies).

On the plus side if you do click ‘ok’ on the box above it seems more like unambigous consent versus browser-wrap.

Given all the above though it’s not clear to us whether this consent model is GDPR compliant or not.

Model 3: Cookie-banner opt-in consent (10% of websites)

Again this is a popup banner at the base or top of the page. We found this on far fewer lawfirm websites, around 10%.

Does cookie-banner opt-in consent meet GDPR requirements?

This model seems more likely to be compliant than either browser-wrap or cookie-banner implicit consent as it’s both unambiguous and gives a clear and easy opportunity to decline cookies.

That said, the implementations we’ve seen and tested on lawfirm websites come with some important side-effects:

- Google Analytics (GA), in most websites we’ve seen with this consent model, GA’s not activated unless someone actively accepts cookies via the banner (GA normally uses cookies). By default, visitors to these firm’s websites are not recorded in any way: where they’ve come from (geographically or via other websites), what pages they’ve looked at and the sequence, and whether they are returning visitors or not. In our view, based on the business advantages foregone of a decent analytics implementation, this is a significant ongoing cost to pay.

- Acceptance is not re-offered. So once a user declines cookies that user will not be tracked in future.

- A permanent cookie is often set on the visitor’s browser to indicate cookies aren’t accepted (yes, you did read that correctly). Of course the alternative to setting a cookie is that you must decline cookies every time you visit the site, probably almost guaranteed to annoy visitors who care enough about privacy to decline cookies in the first place…

- Cookies are often placed anyway by plugins/integrations on the website even if cookes are denied by the visitor. Nearly all sites we tested with this model had some cookies that just ignored the denial. For example cookies were placed by content sharing plugins or underlying website infrastructure like security or load balancing.

Some sites using cookie-banner opt-in consent did try to minimize some of these potential harms to their analytics and user experience. For example, we saw instances of cookie-banner opt-in consent only being offered to visitors coming from European IP addresses (geo-location). However geo-location is imperfect, as you can be accessing from your corporate network in Singapore but exiting onto the web from a corporate firewall in Hamburg. Or for that matter you can simply be a European citizen travelling outside Europe.

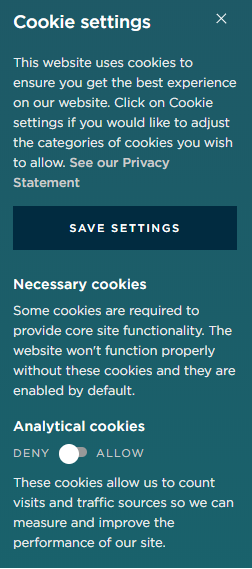

Some sites implementing cookie-banner opt-in consent also attempted to give visitors options for each cookie type being set (see example at right) but given the number and range of cookies being set this could get complicated for users and websites.

So is there any cookie consensus amongst large lawfirms?

It seems consensus is limited to two areas.

Firstly, every lawfirm site is typically using cookies and many in a big way (many of the larger sites we looked at were placing 10+ cookies on visitor browsers and often had multiple Google Analytics accounts too).

Secondly, cookies were typically referenced in the privacy statements or banners, implying at least that lawfirms view cookies as important when it comes to data privacy.

What’s the best GDPR cookie consent model then?

All three consent models detailed above seem problematic mainly because it’s just plain difficult for firms to reconcile what GDPR seems to want with cookies being such a key piece of website wiring.

This is even acknowledged in European Commission discussion about cookies. For example when the Data Protection Working Party says

.. many “logged in” users expect to be able to use and access social plug-ins on third party websites. In this particular case, the cookie is strictly necessary for a functionality explicitly requested by the user..

If we were forced to pick one of these three consent models we’d probably go with Model 2, cookie-banner implicit consent, and put up a banner saying something along the lines of ‘we use cookies – if you continue using the site they’ll be placed on your machine‘. And we’d track that first landing page too (not wanting to forego the valuable knowledge of where people entered our website).

But the individual cookie settings option graphic (above right) might suggest a better answer: differentiating different types of cookies.

It’s a bit of a cliffhanger ending but a more nuanced question about cookie consent might be a) should all cookies fall under GDPR and b) if not, which ones do you need explicit consent for in the first place (Hint: in standard implementations Google Analytics doesn’t in our opinion)? You can then use Model 3’s cookie-banner opt-in only with those cookies that require it.

And all without damaging your website wiring.

Photo of happy cookies by Stevepb CC